This blog post is an attempt to round up the discussion at a session I chaired at the BIG Event in July*.

BIG is a skills-sharing network for individuals involved in the communication of science, technology, engineering and maths (STEM) subjects. It’s been around for 21-25 years in some form and initially involved a core group of exhibit fabricators. In more recent times, the community has diversified to include far more university STEM engagement staff and in the years since my first BIG Event (too long ago to remember) the network has certainly had far more ‘show’ or ‘demo’ developers and performers than exhibit developers.

This year, hosted by the excellent Centre for Life in Newcastle, I wanted to get exhibits back on the programme so proposed the session “Exhibits: innovate or evolve?”.

What I was looking to provoke was a conversation about how we are thinking about exhibits and exhibitions in 2017. I wanted to discuss what has changed in the way we think about exhibits in the last 10 years, what we have learned about the way people interact with exhibitions and exhibits. What is ‘in fashion’ and ‘out of fashion’ and why? What do materials, electronics, technology and manufacturing enable us to do now that we couldn’t do ten years ago?

The Panel

I started by inviting a panel of three speakers with experience in the field and planned to open this discussion to the floor for hopefully more thoughts and ideas.

My first speaker was Andy Lloyd, Head of Special Projects at the Centre for Life. He joined the centre in 2004 to oversee Life’s first major exhibition redevelopment. Since then all the galleries have been changed, with the opening of the under 7s area in 2011, Curiosity in 2012, Experiment Zone in 2015 and Brain Zone in 2016. I had already had conversations with Andy about the evolution of his thinking about exhibits and wanted to explore this more in a group conversation.

The next speaker was Bethan Ross, a Senior Audience Researcher and Advocate for the Science Museum group. I wanted an SMG speaker particularly to talk about the development of Wonderlab, both at the Science Museum in London and at the National Science and Media Museum in Bradford. It was also good to be able to talk about the body of knowledge of visitor studies. Bethan’s role is to advocate for the audience on exhibitions, galleries and learning projects with an emphasis on interactives, digital interpretation, and maker spaces. This involves keeping up to date with the latest research and evaluation from the museum and elsewhere as well as managing prototyping of digital and mechanical interactives.

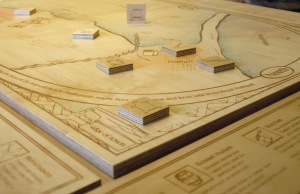

And finally, an exhibit fabricator; Ken Boyd set up FifeX in 2002 and has been designing, building and installing bespoke interactive exhibits ever since. They work with visitor centres, museums and science centres up and down the UK and abroad. As an ‘exhibit builder’, they see all angles of the exhibit development process and how their clients’ requirements continue to evolve.

What has changed in the way we think about exhibits in the last 10 years?

To start Bethan told us a little about the aims and objectives of the exhibits in the Wonderlab Bradford project. She talked about the overall aims for the exhibition, selection criteria for the exhibits and how much this might have differed from Wonderlab in London.

This is interesting and relevant as Wonderlab is the evolution of the old ‘Launch Pad’ at the Science Museum which has itself had a few iterations and can trace its lineage back to the first ‘hands-on’ museum space the ‘Children’s Gallery’ opened in 1931.

Wonderlab in Bradford specifically looks at science related to broadcast media technology, such as sound and light. The driver is to encourage and promote curiosity and questioning; to assist discovery by providing visitors with real physical phenomena that they can manipulate and investigate. i.e. ‘teaching’ scientific skills and habits of mind rather than specific scientific content. Wonderlab in London however, set within the broad context of the collections of the Science Museum London, could never hope to reflect the science of the whole collection. Instead, exhibits were chosen for a range of other criteria around visitor engagement and enjoyment, memorability and efficacy in achieving their learning objectives.

Even within this one case-study, we can see that the question ‘what are interactive exhibits for?’ is highly contextual and can have many answers.

Andy then talked about the changes at Life since 2010. In 2011 they opened a gallery upstairs for under 7’s, designed to stimulate creative play. In 2012 “Curiosity” set out to stimulate specific behaviours and thought-processes through interactive exhibits, rather than deliver information. In 2015 they opened “Experiment Zone”, a family laboratory that boosts people’s sense of identification with science through an authentic lab experience and last year they opened “Brain Zone”, bringing visitors into active neuroscience, psychology and anthropology research. Andy talked about the move to social engagement and personal factors like self-confidence and identity. We all discussed how exhibits can be organised into those imparting information in an ‘active learning’, to those offering an experience or skills (such as experimentation).

At this point, we had a discussion about ‘Science Capital’ – particularly in relation to ‘Experiment Zone’. One of the underlying research findings of the work on Science Capital by King’s College London and the Science Museum in the Enterprising Science project is that although many children were interested in science, those without what has been termed ‘high science capital’ just didn’t see themselves as future scientists. Experiment Zone offers an opportunity for children to dress in lab coats and work on experiments with family members, parents often record this experience in photos which are shared with family and friends with pride and comments relating to possible future identity. This is where exhibits and exhibitions in Science Centres diverge from those in Museums, Heritage Sites and other types of Visitor Centre.

Are interactive exhibits a good way to deliver content?

In the museum and heritage sector, I am a strong advocate for interactive exhibits. I feel that exhibitions and site interpretation engage best when they engage all learning preferences and all the senses. I’m a believer in the power of active learning to engage minds and hands-on activities to vary the pace of a visitor’s experience.

But in a Science Centre, Andy is sceptical about exhibits delivering information. He feels that exhibits can lead to a lot of learning, but this comes from the process of interacting with the exhibit and with other people not the discovery of new information. Bethan advises exhibition teams on both interactive-led and object-led galleries and so was able to talk about the different roles of an interactive. Interactives in object-rich galleries are helping with the interpretation of the object or story, whereas interactives in interactive-only spaces are more about the experience itself.

We had a discussion at this point with the floor about how important it is whatever your type of project to have clear learning outcomes for exhibits. We generally all felt that using the GLO framework is a good way to emphasise that these can be emotional and attitudinal outcomes, not just knowledge and understanding.

Sharing best practice

The next discussion was about whether we are building a body of knowledge that can be reused and applied.

Bethan felt we had a better understanding of the importance of clear objectives and better prototyping and spoke about the advantage of audience research focussed department meaning within the SMG they can devote time to digesting this body of knowledge and disseminating.

Andy mentioned one of the privileges of his position is that he gets to visit other centres to see their exhibits and talk to their staff about their thinking. Study visits are often about watching people not exhibits, who’s using which exhibits, and not. However, everyone agreed that isn’t always enough and international travel is expensive. Ken and other fabricators strongly suggest buying in some of their time to discuss ideas at a very early stage, or even just calling for an informal (free) chat. Other routes are to explore ExhibitFiles.org and other online resources such as exhibit catalogues and reviews of new exhibitions. Working with a variety of smaller clients, Ken feels like they reinvent the wheel a lot and should be thinking of new ways (perhaps through BIG?) to develop a rule book for exhibit design!

From the floor, we had questions from science engagement staff with no experience of exhibit development asking about how to start developing an exhibit, and how to estimate costs for funding bids. Again, the recommendation was to have an early conversation with a fabricator. There was a strong feeling from the floor about the challenges of tendering and the processes associated with large capital funding and how these might limit creativity and early R&D.

New approaches?

Something I noticed at the Wonderlab in London was the use of named artists on some exhibits. I asked Bethan about the thinking behind these and we discussed the advantages of working with artists to achieve something different and a new perspective. They also specifically worked with local artists to help connect to the local area and local audience.

Ken has also worked a lot with artists and finds skills the same for developing installation art for places like hospitals –e.g. the Southern General in Glasgow. Andy has also used art as exhibits, both in his time at the Science Museum and at Life. The best example at Life being “Crystal Brain” in the Brain Zone exhibition where visitors can wear sensors and see their brainwaves control a visual output. Because of the importance for an exhibit of this type to avoid being in any way diagnostic or mistaken for diagnosis, the output of Crystal Brain is very abstract. Interestingly, visitors with the highest Science Capital often find this frustrating as they want to know exactly what is being measured and shown, whereas lower Science Capital visitors are happy to just explore the phenomena without further information.

At this point, I feel I should apologise for the length of this blog post and indeed, this is the point where our session ran out of time. Things we didn’t get a chance to discuss include; graphics, the role of floor staff, managing visitor behaviour, maintenance and robustness issues, technological advances, design and fabrication processes.

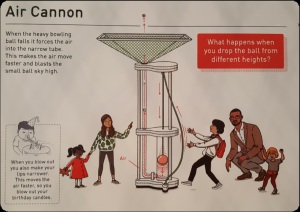

I had wanted to ask Bethan about the graphic illustrations in Wonderlab. They added illustrations and also prototyped these as well as the textual instructions. It helped to bring people into the gallery (representation) and also assisted in parental scaffolding – allowing them to talk less about the procedural and more about the science.

And I think there’s a whole session to be run at a future BIG Event on exhibit floor-staff. As Andy pointed out, exhibits have limitations that are largely set by the limits of technology and the imagination of the developers. People can observe and respond to visitors immediately and answer their questions and requests for help. Unfortunately, while they have a low capital cost they are the most expensive part of science centre operations so often we have to develop exhibits that can work without human intervention. But they still provide the best visitor experience over any technology.

Bethan mentioned that staff interactions often come out as a key point in summative evaluation. Wonderlab London is permanently staffed, Bradford might not always be. The role explainers play in a gallery is something SMG are looking at. Visitors like a bit of reassurance and to know they can ask for help if I need it. Ther are practical and safety reasons and many visitors appreciate the personal contact. Research shows that families/parents see explainers as scientists or science role-models of a relatable age for their children, which again feeds into thinking about raising Science Captial.

The biggest takeaway for me from this conversation was that there is so much more conversation still to be had. It felt like there was a real appetite for it at the BIG Event and I hope we can see more sessions at future Events on different aspects. There may also be potential for a re-boot of the fabricators’ group within BIG and some way of sharing best practice in this area in the current context.

*As we didn’t record the session or have a dedicated note-taker, I offer unreserved apologies to anybody who feels misrepresented in this post, or that the session is misrepresented.